How I help hospitals improve diagnosis detection

Across finance, healthcare, e-commerce, and social platforms, the same core algorithmic principle applies: efficiently discovering meaningful co-occurrence patterns at scale. PCY enables this by reducing memory, computation, and noise—turning raw data into actionable insight.

AI/ML

1/19/20264 min read

When hospitals approach me, they usually don’t ask for an algorithm.

They ask questions like:

“We have years of patient data, but patterns are hard to see. How do we detect meaningful symptom combinations early?”

The challenge isn’t data availability — hospitals have plenty of it. The challenge is transforming raw clinical records into actionable diagnostic signals without overwhelming clinicians or infrastructure.

From a data perspective, the goal is to discover which symptoms, diagnoses, or treatments frequently occur together across patient visits — reliably and at scale.

How I model the problem

Before choosing any algorithm, I first decide how the clinical reality should be represented mathematically.

This modeling step is where most of the value is created.

Here’s how I frame it:

Transaction → One patient visit

Each visit captures a snapshot of observed symptoms, tests, and treatments at a specific moment in time.Items → Symptoms, diagnoses, or medications

Each clinical observation becomes a discrete item that can participate in patterns.Itemsets → Co-occurring clinical signals

If symptoms appear together repeatedly across visits, they may indicate an underlying condition or care pathway.Support threshold → Clinical significance filter

I define a minimum number of patients in which a pattern must appear before it is considered meaningful.

This framing lets me translate an open-ended medical question into a precise, testable data-mining problem.

Why PCY is needed in healthcare analytics

Once the problem is modeled this way, a constraint becomes immediately obvious.

Hospitals operate with:

Thousands of symptoms, lab tests, medications, and procedures

Millions of patient visits

Extremely sparse combinations

If I attempted brute-force counting of every possible symptom pair, the system would collapse under combinatorial load.

That’s why I choose PCY.

PCY allows me to:

Filter unlikely symptom pairs early

Use hash buckets as a low-cost pre-screening mechanism

Reserve exact counting only for combinations that show real promise

This design choice is about respecting both clinical complexity and computational reality.

What hospitals ultimately get

By structuring the problem and applying PCY, I produce:

Frequent symptom pairs → recurring clinical patterns

Candidate pairs → combinations worth clinical attention

Final frequent pairs → evidence-backed signals for diagnosis support

💡 Medical value: improved diagnostic awareness, earlier detection of patterns, and more consistent treatment planning.

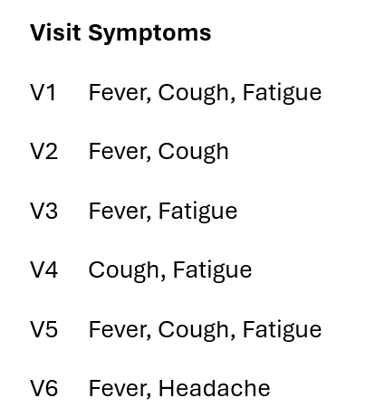

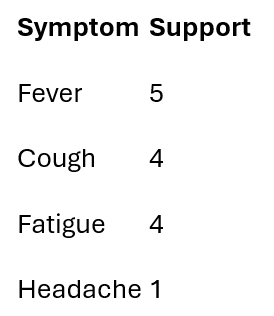

Step 1: Patient visits as transactions

Once the modeling is clear, I move to data preparation.

I treat each patient visit as a transaction.

To make this computationally efficient, I encode symptoms numerically:

1 = Fever

2 = Cough

3 = Fatigue

4 = Headache

I then define:

Minimum support = 3

This means a symptom or symptom pair must appear in at least three patient visits to be treated as clinically relevant rather than incidental.

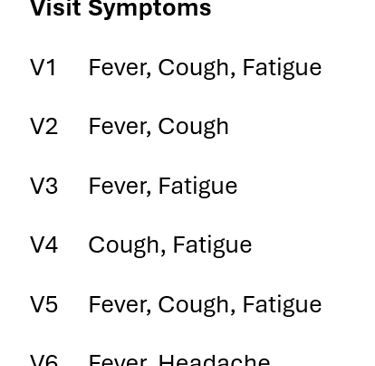

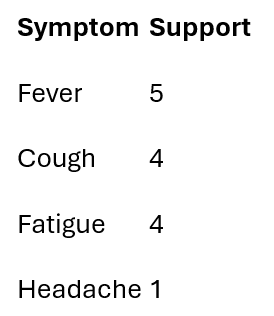

Step 2: Single-symptom support (what I eliminate first)

Before looking at interactions, I intentionally simplify the problem.

I count how often each symptom appears on its own.

Only symptoms meeting the support threshold survive.

Frequent symptoms: {Fever, Cough, Fatigue}

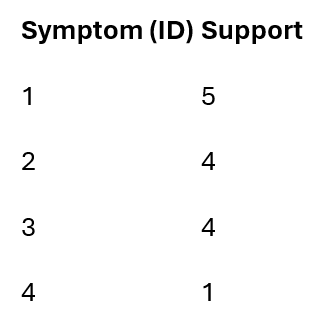

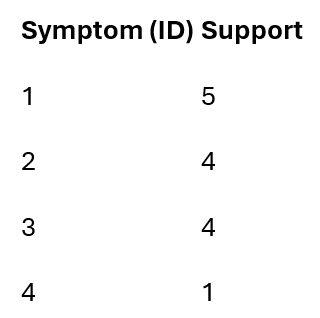

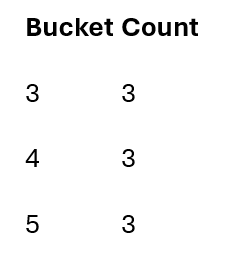

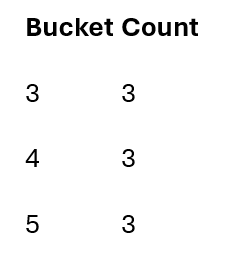

Numeric support view:

I drop Headache at this stage — not because it lacks clinical importance, but because this specific dataset doesn’t provide enough repeated evidence to support reliable co-occurrence analysis.

This early pruning is deliberate: it prevents rare cases from distorting broader diagnostic patterns.

Step 3: PCY hashing (how I control combinatorial growth)

Now I apply the first PCY pass.

Instead of storing all symptom pairs explicitly, I hash pairs into buckets and count bucket frequencies.

Example hash function:

h(i,j) = (i + j) mod 7

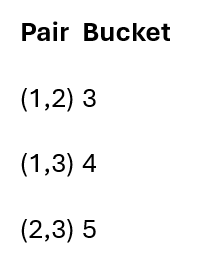

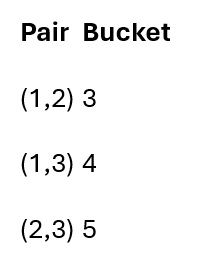

Hashed pairs:

As visits are processed, bucket counts accumulate.

Only buckets meeting the support threshold survive.

This step filters out:

Rare symptom combinations

Noise from isolated cases

The majority of unnecessary computation

Hash collisions are acceptable here — they only make the filter conservative, not incorrect.

Frequent items after pass 1: L1 = {1,2,3}

Step 4: Pass 2 – How I define candidate symptom pairs

Now I deliberately narrow focus.

I form candidate pairs (C₂) using two strict criteria:

Both symptoms must be individually frequent

Their hash bucket must be frequent

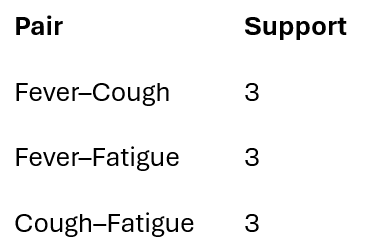

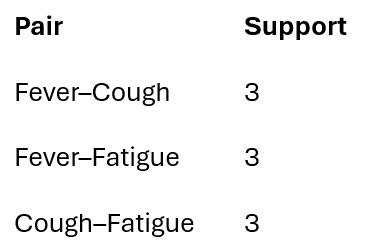

Candidate pairs:

Fever–Cough

Fever–Fatigue

Cough–Fatigue

Formally:

C2 = {(1,2),(1,3),(2,3)}

This ensures that every pair I examine has already passed multiple evidence filters.

Step 5: Final counting (where I trust the result)

Only now do I perform exact counting — and only on candidate pairs.

Final frequent symptom pairs: L2 = {(1,2),(1,3),(2,3)}

These are symptom combinations that consistently co-occur across patient visits, not statistical coincidences.

What this means clinically

Because of how the problem is modeled and filtered, doctors can now see:

Recurring symptom clusters

Early warning patterns

Evidence-based correlations grounded in patient data

Nothing here is inferred, assumed, or imposed by the model — it simply surfaces what repeatedly occurs.

Medical value

By carefully modeling the problem before applying algorithms, I help hospitals:

Detect diagnostic patterns earlier

Reduce cognitive load on clinicians

Scale pattern discovery across millions of records