How I help financial institutions identify fraud patterns

Across finance, healthcare, e-commerce, and social platforms, the same core algorithmic principle applies: efficiently discovering meaningful co-occurrence patterns at scale. PCY enables this by reducing memory, computation, and noise—turning raw data into actionable insight.

AI/ML

1/26/20263 min read

When financial institutions come to me about fraud detection, they rarely start with algorithms.

They usually ask something like:

“We see suspicious transactions, but it’s hard to tell what’s truly abnormal versus normal customer behavior.”

That distinction matters.

Fraud detection isn’t about labeling everything unusual as fraud — it’s about first understanding what normal behavior looks like at scale, and then flagging what deviates from it.

Banks process millions of transactions per day. Without a principled way to define “normal,” fraud systems either:

Miss real threats, or

Overwhelm analysts with false positives

How I model the problem

Before I touch any algorithm, I decide how banking activity should be represented.

This modeling step is critical, because fraud detection depends on context, not isolated events.

Here’s how I structure it:

Transaction → User session

One banking session or customer activity window (e.g., login → actions → logout)Items → Actions

Actions such as ATM withdrawal, online transfer, password change, foreign loginItemsets → Behavioral patterns

Actions that frequently occur together define normal behaviorSupport threshold → Normality filter

A pattern must occur often enough to be considered expected behavior

Once framed this way, fraud becomes a deviation problem:

Anything outside frequent patterns is potentially suspicious.

Why PCY is needed in banking systems

After modeling the problem, a hard constraint appears immediately.

Banks deal with:

Millions of daily sessions

Dozens of possible actions per session

Explosive combinations of action sequences

Brute-force counting of all action pairs doesn’t scale.

That’s why I use PCY.

PCY allows me to:

Identify frequent, normal behavior patterns efficiently

Filter rare or anomalous combinations early

Scale fraud analysis without blowing up compute or storage

What banks get from this approach

By combining careful modeling with PCY, I produce:

Frequent action pairs → baseline customer behavior

Missing or rare pairs → potential fraud signals

A clear definition of normality grounded in data

💡 Business value: reduced fraud losses, faster detection, and scalable analysis without overwhelming fraud teams.

What banks are really asking

Underneath all fraud tooling, the core question is simple:

“What transaction behaviors normally occur together?”

Once that’s answered, fraud detection becomes much easier:

Transfers without login?

Unusual action combinations?

Sudden spikes in rare behaviors?

Those are no longer vague concerns — they become measurable deviations.

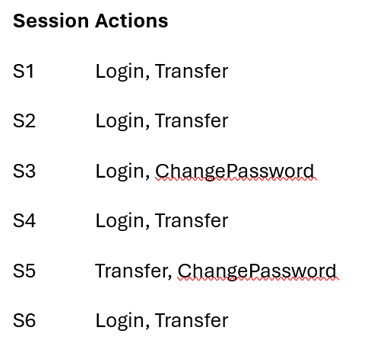

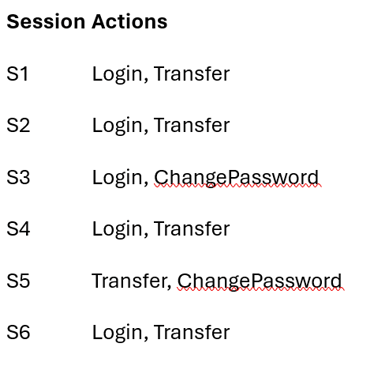

Step 1: Transaction sessions as transactions

I start by modeling each banking session as a transaction.

I then define:

Minimum support = 4

This means an action pattern must appear in at least 4 sessions to be considered normal behavior.

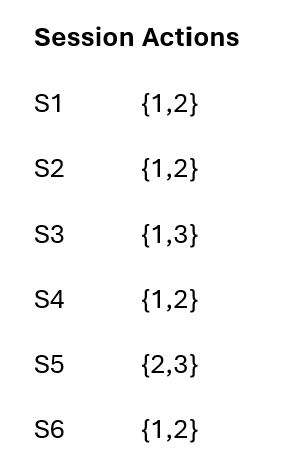

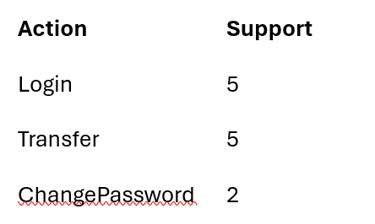

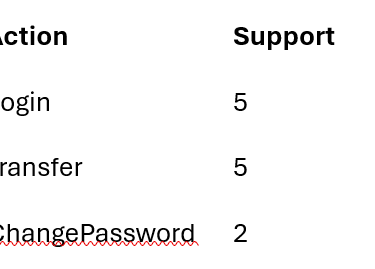

Step 2: Pass 1 – Single action support (what I eliminate first)

Before looking at combinations, I determine which actions are common enough to matter.

Only actions meeting the support threshold survive.

Frequent actions: {Login, Transfer}

Numeric view:

Formally: L1 = {1,2}

ChangePassword is dropped at this stage — not because it’s unimportant, but because it doesn’t occur often enough to define normal session behavior in this dataset.

This step dramatically reduces noise and future computation.

Step 3: PCY hashing (how I define normality efficiently)

Now I apply PCY’s first pass.

Instead of explicitly counting all action pairs, I hash them into buckets and count bucket frequency.

Hashed pair:

Pair Bucket

(1,2) 3

Bucket support:

(Login, Transfer) appears in 4 sessions

Since the bucket meets the minimum support threshold, it is marked frequent.

This step ensures:

Normal behavior survives

Rare combinations die early

Computation stays bounded

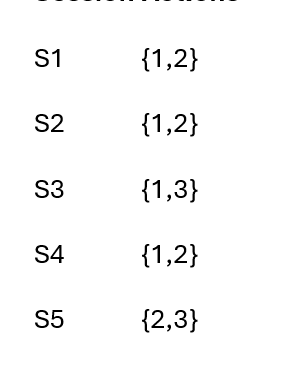

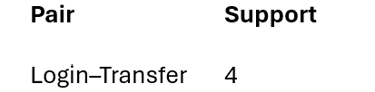

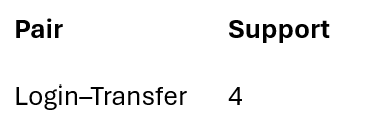

Step 4: Pass 2 – Candidate action pairs

Next, I construct candidate pairs (C₂).

Rules:

Both actions must be frequent

Their hash bucket must be frequent

Candidate pairs: C2 = {(1,2)}

There is only one pair worth examining further.

Step 5: Final counting (what I trust)

I now perform exact counting — but only for candidate pairs.

Pair Support

(1,2) 4

Final frequent pair:

L2 = {(1,2)}

Translated back to actions:

This pair defines normal customer behavior.

Fraud insight (where detection happens)

Because I’ve clearly defined normality, fraud signals become obvious.

When the bank sees:

Transfer without Login

ChangePassword + Transfer spikes

Action combinations not in L₂

🚨 Alerts are triggered.

These alerts aren’t heuristic guesses — they’re grounded in statistically frequent behavior patterns.

Business impact

By modeling the problem correctly and using PCY:

Banks define normal behavior empirically

Fraud detection becomes deviation-based, not rule-heavy

Systems scale across millions of sessions per day

PCY doesn’t detect fraud directly.

It defines normality — and that’s what makes fraud visible.