How I design eCommerce recommendation systems that actually convert

Across finance, healthcare, e-commerce, and social platforms, the same core algorithmic principle applies: efficiently discovering meaningful co-occurrence patterns at scale. PCY enables this by reducing memory, computation, and noise—turning raw data into actionable insight.

AI/ML

5/8/20244 min read

When clients come to me asking for “recommendations,” what they usually mean is:

“We have a lot of data, but we don’t know which product combinations actually matter.”

That distinction is important.

Most teams don’t have a data problem — they have a signal problem. They’re drowning in transactions, SKUs, and clickstreams, but they don’t know where to focus. The instinctive response is usually: “Let’s analyze everything.”

That’s the mistake.

Analyzing everything at once doesn’t scale, doesn’t converge, and — most importantly — doesn’t translate into higher conversion rates.

Instead, I focus on a much simpler question:

Which products do customers actually buy together often enough that it’s worth acting on?

To answer that efficiently, especially at scale, I rely on frequent itemset mining using the PCY algorithm.

Why PCY is needed (and why naïve approaches fail)

In a real e-commerce environment:

The store may have millions of products

Each order may contain only a handful of items

The number of possible product pairs is astronomically large

If you try to count every possible pair directly, you run into a classic combinatorial explosion. Most of those pairs will never appear together, but you still pay the computational cost of tracking them.

PCY exists specifically to avoid this trap.

By using hashing as an early filtering mechanism, PCY lets me quickly eliminate unlikely product combinations before they ever become expensive to count. The algorithm is intentionally conservative: it would rather keep a few extra candidates than accidentally throw away a meaningful pair.

That tradeoff is exactly what you want in production systems.

What this produces in business terms

From a business perspective, PCY gives me three useful layers of output:

Frequent pairs → the raw signal behind “Customers who bought X also bought Y”

Candidate pairs (C₂) → combinations worth examining further

Final frequent pairs (L₂) → the recommendations that actually show up on product pages

💡 Business value: higher conversion rates, better upselling, and more revenue — without blowing up compute costs.

How I model the problem

Let’s ground this in this concrete example.

Imagine an Amazon-like online store that wants to recommend products that are frequently bought together. The modeling choices are straightforward but intentional:

Each customer order becomes a transaction

Each product becomes an item

A support threshold defines what “frequent” actually means

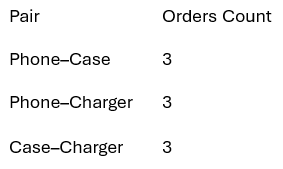

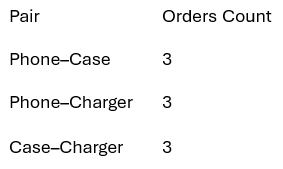

In this example:

Support threshold = 3

A product pair must appear in at least 3 different orders to be considered meaningful

This threshold isn’t arbitrary — it’s a way of saying: “If this doesn’t happen repeatedly, we don’t trust it enough to recommend.”

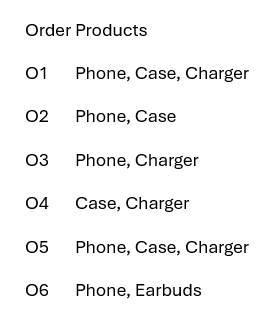

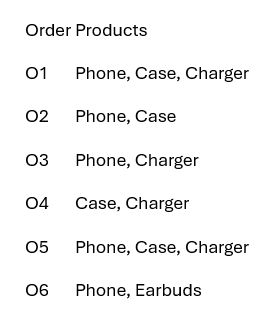

Here is an example transaction data

Each row represents a real customer decision. No assumptions, no inferred behavior — just what people actually bought together.

To make the algorithm efficient, I encode products numerically:

1 = Phone

2 = Case

3 = Charger

4 = Earbuds

This encoding doesn’t change meaning — it just makes hashing and counting feasible at scale.

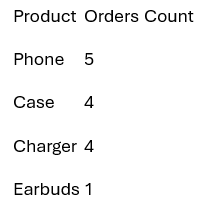

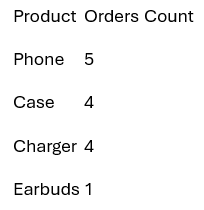

Step 1: Count single-item support (popular products first)

Before even thinking about product pairs, I ask a simpler question:

Which individual products show up often enough to matter?

Anything below the support threshold is dropped immediately.

This step is critical, and often underestimated.

Why drop items early?

Because if a product rarely appears at all, recommending it alongside something else introduces noise. From a systems perspective, this step also produces massive savings at scale — every item removed here prevents an explosion of useless combinations later.

Earbuds disappear from the analysis, and that’s exactly what we want.

Step 2: Hashing pairs to reduce pair explosion (PCY pass 1)

Now comes the core PCY idea.

Instead of explicitly counting every possible product pair, I hash pairs into buckets and count bucket frequency.

Example hash function:

h(i,j) = (i + j) mod 5

As transactions stream through the system, I hash each pair and increment the corresponding bucket. After the first pass, I only keep buckets whose counts meet the support threshold.

Why this works:

Buckets act as a cheap approximation of pair frequency

Infrequent buckets cannot contain frequent pairs

Hash collisions don’t break the algorithm — they just make the filter conservative

This allows me to:

Avoid storing millions of pair counters

Keep only promising combinations

Maintain scalability as data grows

Step 3: Counting only what matters (candidate pairs C₂)

At this point, I define candidate pairs very strictly.

I will only count a pair if:

Both items are individually frequent

Their hash bucket is frequent

This double filter is where most of the computational savings happen.

Candidate pairs:

(Phone, Case)

(Phone, Charger)

(Case, Charger)

Everything else is discarded without regret.

Step 4: Exact counting (PCY pass 2)

Only now do I perform exact counting — but on a dramatically smaller set.

These pairs meet the support threshold and become my final frequent pairs (L₂).

These are not theoretical correlations — they are patterns grounded in repeated customer behavior.

Why these are the only pairs I trust?

At this point, every remaining recommendation has passed:

Popularity filtering

Hash-based pruning

Exact frequency validation

That’s why I trust them enough to surface to users.

Anything weaker risks misleading customers, cluttering the UI, or diluting conversion impact.

Business outcome

This approach directly powers:

“Frequently bought together” widgets

Bundle discount logic

Cross-sell and upsell recommendations

And most importantly — it scales.

Without PCY-style pruning, recommendation systems buckle under real-world data volumes. With it, you get a clean signal, predictable performance, and recommendations that actually convert.